Of all the scenarios emergency preparedness professionals face—whether as elected officials, private-sector crisis management teams, or staff in an emergency operations center (EOC)—one is a particular challenge: multi-incident simultaneous response and recovery (MISRR). As a phenomenon within emergency management, MISRR emerges when an entity (governmental, private, or nonprofit) conducts multiple incident or event response and recovery efforts simultaneously. Using funding as an indicator for the largest U.S. disaster declarations, it is clear that states and territories such as Puerto Rico, New York, the U.S. Virgin Islands, Texas, Louisiana, and California have regularly experienced MISRR over the past two decades. In these locations, managing simultaneous response and recovery efforts for multiple disasters may reflect normal operations, given their risk environment. However, as demonstrated by hurricanes Helene and Milton in 2024, jurisdictions unaccustomed to compounding incidents requiring simultaneous response and recovery can bolster their readiness by proactively examining and preparing for unique challenges posed by such a scenario.

Background: Response and Recovery for Hurricanes Helene and Milton

The distinct “mission areas” within the National Preparedness Goal from the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) and literature related to the “phases” of emergency management may support the conclusion that response and recovery are siloed functions—with recovery only beginning once response operations have formally concluded. While such an approach may be sufficient for small-scale and non-complex incidents or events, the current risk environment has pushed entities to conduct response and recovery operations concurrently. When an entity conducts simultaneous response and recovery, they are only one incident away from meeting the definition of a MISRR scenario. This is what Florida and other states in the U.S. Southeast recently experienced. While still actively responding to and starting recovery efforts for Hurricane Helene (landfall September 26, 2024), the state of Florida was impacted by Hurricane Milton (landfall October 9, 2024).

Cope and Succeed

Whether compounding incidents are a regular or a rare occurrence for an organization, the following concepts may help improve outcomes. As with any preparedness measure, it is beneficial to consider and adopt such concepts during the pre-incident phase.

Thinking Multi-Incident

FEMA’s Threat and Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment (THIRA) provides communities a structured analytical technique to identify risk (including context) and establish capabilities to manage this risk (Figure 1).

Utilizing worst-case scenario planning, take the threats identified from the THIRA process and consider the ramifications of multiple threats occurring simultaneously. Such concurrent incidents could manifest as a black swan (i.e., an unpredictable incident with catastrophic impact), from cascading disasters (i.e., when an initial incident causes subsequent significant incidents), or when faced with threats in rapid succession (i.e., compounding incidents) such as hurricanes Helene and Milton. The objective of this is to plan, train, exercise, and thereby promote multi-incident thinking with emergency management professionals. The threats identified in the THIRA process cannot be considered in isolation. This is especially the case for pre-incident emergency preparedness plans or business continuity plans that also assess and address threats independently. Instead, embracing a worst-case planning methodology calls for assessing which threats are likely to occur simultaneously and how their convergent impact is greater than the sum of its parts (e.g., hurricanes during pandemics or fire suppression during civil unrest). This results in both plans and personnel reflecting enhanced knowledge of the interplay between multiple incidents.

An effective methodology to examine an organization’s readiness for MISRR is a discussion-based exercise, such as a tabletop exercise. This is a low-cost and low-consequence environment that assesses whether an organization has the necessary plans and capabilities. Such exercises encourage emergency management professionals to think multi-incident.

Staffing: Response and Recovery

Within the premise of MISRR, response and recovery activities take place at the same time for a portion of the incident period. Therefore, building a sustainable staffing plan that can fulfill both functions is key. Principles from the Incident Command System (ICS) may be considered, such as the unified area command, where incident commanders report up to one centralized area command. Task saturation is likely to be too high to assign significant response and recovery workloads to the same resource. Therefore, the ability to build a concurrent staff structure focused on unique response and recovery activities is needed. If the finance section chief faces two (or more) active responses, they might not accomplish time-sensitive steps in the FEMA Public Assistance process for recovery. Therefore, assigning or mobilizing recovery-focused personnel within the section is key. Such augmentation can stem from internally trained staff, local or intrastate mutual aid, the Emergency Management Assistance Compact (EMAC), or an Incident Management Team (IMT).

Incident commanders should prepare for and plan the staffing solutions needed to begin recovery as soon as possible. At the same time, they should recognize that, in a MISRR scenario, the staff normally tasked with recovery duties are occupied with response for a second incident. The logic behind this concept is to not delay recovery but instead begin recovery as soon as possible via a sustainable staffing approach. The result is more rapid recovery with minimal impact on response efforts, which leads to faster community lifeline restoration and increases the flow of critical recovery aid.

Do Not Forget ICS During Recovery

ICS principles are a staple in incident response within the U.S. Such a structured and standardized approach should not be discarded during recovery operations. The highly systematic and routinized principles outlined in ICS enhance recovery. This is especially the case in MISRR. When multiple incidents are active, maintaining structure is crucial, during both response and recovery. Recovery operations should be included in an Incident Action Plan (IAP), and incident-specific data can be captured in situation reports. Additionally, ICS provides helpful structures to expand and develop recovery efforts into focused branches, divisions, and groups.

Tracking Cost

During a MISRR, the ability to keep each incident separate—in terms of operations, logistics, finance, and planning—is critical. For example, responding to two or more simultaneous incidents creates expenses that must be tracked separately. Utilizing pre-planned cost-tracking systems that allow for the separation of different incidents is needed for the immediate response and to support recovery. This is commonly achieved via disaster-specific charge codes for invoices or purchase cards, which can connect all expenses for a given incident. Accurate and separate incident cost-tracking ensures that the incident command knows the daily and total cost (for each incident), which empowers those working on recovery efforts.

Workspace and Schedule

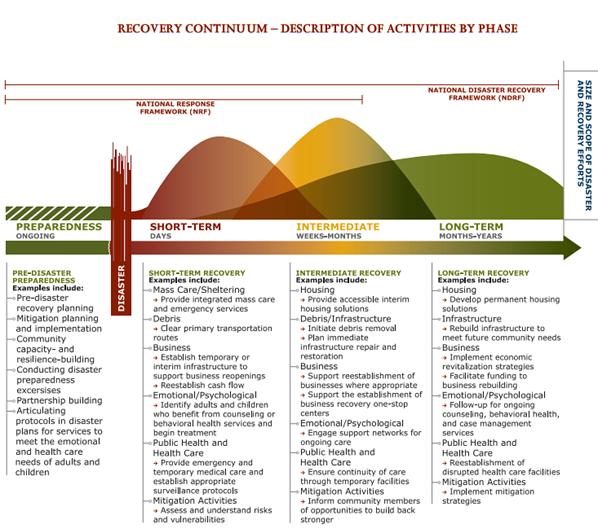

Work location and schedules for recovery staff should be critically examined. While integrating into the ongoing incident—via operational period briefings and inclusion in the IAP—the bulk of recovery staff may be best suited to work in their own space rather than the main EOC floor. Having their own space allows for a more focused environment for the precise work associated with recovery—such as cost validation and calls with vendors related to sensitive financial matters. Additionally, this ensures the EOC has the capacity (or open seats) for additional response resources in the event of additional incidents or an extended response period. Finally, evaluate the schedule or “battle rhythm” for recovery staff. Even if the duties (i.e., operational tempo) of response start to slow, maintaining a full work schedule or perhaps even increasing the schedule for recovery staff is worth consideration. In fact, the National Disaster Recovery Framework illustrates that long-term recovery efforts increase while response efforts conclude. Therefore, an inverse relationship exists between the efforts (and schedules) of response and recovery staff: When the response deescalates, recovery escalates (Figure 2).

Conclusion: Prepare Before

For many of the most disaster-stricken states and territories in the U.S., managing multi-incident, simultaneous response and recovery has become business as usual due to the threat environment. Entities are more likely to have experience, plans, and capabilities to be successful when faced with such a scenario. Five considerations have been outlined for entities that do not regularly need to conduct simultaneous response and recovery for two or more incidents. By understanding the impact of multiple incidents, developing agile staffing plans, utilizing ICS during recovery, maintaining accurate cost tracking, and critically assessing how to best utilize recovery staff, entities can enhance their readiness to serve stakeholders more effectively during a MISRR scenario.

Tucker Berry

Tucker Berry is a disaster response and recovery consultant. He formerly served as a deputy section chief at the Texas Department of State Health Services’ State Medical Operations Center and supported 35 incidents, including state and presidential disaster declarations. Prior to government service, he completed a master of international affairs and was a research assistant at the Texas A&M University Bush School of Government and Public Service. He is a graduate of the Preparing to Lead in Crisis program from the National Preparedness Leadership Initiative at Harvard University.

- Tucker Berryhttps://domesticpreparedness.com/author/tucker-berry