A crisis can be described as unpredictable and often sudden. It can be life-threatening and life-changing, which creates a high level of uncertainty and leaves people feeling out of control and overwhelmed. Some crises can be almost universal, with many people having similar experiences – for example, the COVID-19 pandemic, a significant incident with loss of life, a foreign or domestic terrorist attack, or a system collapse such as the financial infrastructure.

A crisis can also be personal, such as a car accident, a sudden death of a family member, a job loss, or other life disruptive event. Whether it affects many people or is personal, there are predictable elements to crisis and the psychology behind how and why people react. By knowing how to define a crisis, why people react the way they do, and how to manage it, people can mitigate their reactions and lessen the time they feel overwhelmed and out of control.

Behavioral Reaction Phases

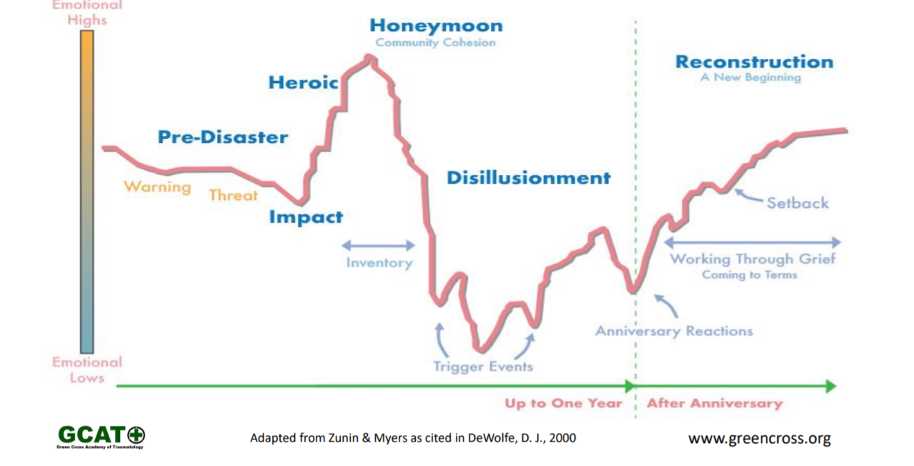

The psychological response to a crisis is eerily predictable and can be anticipated, whether exploring it from a personal or a professional perspective. There is a pattern of behavioral and psychological reactions.

Pre-Disaster Phase

Start by thinking about a typical day in the regular pattern of life, which can be called pre-crisis or pre-disaster. For a natural disaster, there might be a warning that something is coming. The warning spurs attention to new information that may have an impact. When new information arrives, people can either hear it or ignore it, but, on some level, they react to it. When that warning becomes a real threat, the senses become alert, and people respond to both the threat and the impact.

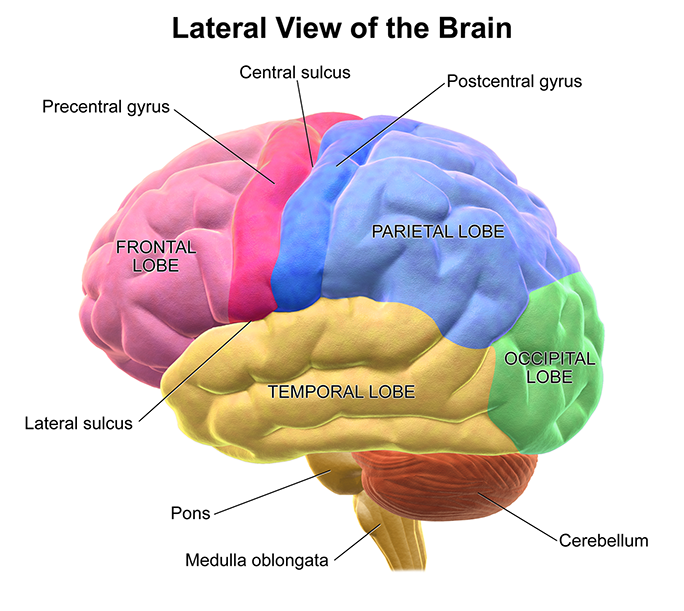

Whether there is a warning or not, at this point, the personal senses are both sharpened and muted due to the physiological response of survival chemicals being released into the body to impact thoughts, feelings, actions, and senses. This response affects heart rate, digestion, vision, actions, memory, judgment, critical thinking skills, and more – often called the fight, flight, or freeze reaction.

Sometimes, reactions are easy to identify. At other times, they may be less noticeable, even when they are happening. For example, imagine being handed a note that says to call home because of an emergency, and the phone number or even where the phone is slips the mind. In a different crisis, the reaction could be much more extreme, including not reacting at all (shock), or a spontaneous action such as running into the incident without thought to personal safety.

Heroic Phase

The next set of predictable reactions includes being able to take control and manage an immediate situation even when it is challenging to imagine doing. Physical strength may increase, which is evident in cases where someone has picked up a car to rescue a stranger who was trapped. Sometimes, families come together in ways they never have before or discover new ways of short-term coping. Efforts such as Boston Strong illustrate this result by recognizing survival and forming community coalitions. When communities unite, it breaks the sense of isolation and vulnerability that can be present in many individuals. During these times, there can be a sense of euphoria and thoughts that anything can be manageable!

Disillusionment Phase

Unfortunately, the Heroic Phase soon gives way to the Disillusionment Phase. There can be a steep dive into darker emotions and behaviors from here. Anger, frustration, blame, and depression are not uncommon. With regard to the COVID-19 pandemic, this phase included people going to their government state houses, angry that officials were asking them to wear masks. Some areas also saw intense civil unrest in this phase of the global crisis.

Reconstruction Phase

Eventually, people adjust and climb back up that emotional ladder to something more comfortable as this new way of being becomes more familiar. Normal is a word that tends to be overused and, in many ways, is inaccurate. It is impossible to travel back to yesterday or the moment before the crisis occurred, so people should not define “normal” in such terms. Normal is just a setting on a dryer! If that is the gauge, it is a set-up for failure. The genuine desire is to be comfortable again, which requires familiarity and the passing of time.

There will be ups and downs as different trigger events happen moving forward. However, the slow climb brings people to a place of less intense emotion and reaction over time. The time for this to happen, though, can be months or even years for some crises and some people.

Psychological and Physiological Reactions

Taking the psychology of a crisis into consideration, emergency preparedness professionals need to understand and acknowledge that during a crisis, people in the community may:

- Take in information differently,

- Process information differently,

- Act on information differently,

- Cannot fully hear because they are juggling multiple facts,

- Are not remembering facts as they usually would, and

- Can misinterpret action messages.

Initially, people can believe the crisis is so large and overwhelming that it creates a feeling of hopelessness and helplessness. There may not seem to be anything anyone can do about it. Hopelessness and helplessness lead to a sense of lack of control that then leads to vulnerability. Add conflicting information or lack of information, which can increase anxiety and emotional distress, and people can become confused, angry, and uncooperative.

As people move through the psychological and physiological response to a crisis, they will get to the stage where they experience relief, recovery, and reorganization. A sense of strength and empowerment can give a new understanding of risk and risk management, add new skills and resources that can manifest as a renewed sense of community, and open new opportunities for growth and renewal. All of this can lead to what is called post-traumatic growth – post meaning after and traumatic meaning a crisis. Growth refers to emerging with new skills and a more profound understanding and appreciation. However, it does not come quickly or easily.

A Critical Role for Leaders and Influencers

Leaders and influencers have an important role in crisis management for themselves, their families, and their organizations. Those around them will be looking to them for guidance and direction. By understanding the pattern of the crisis itself, leaders and influencers are better able to anticipate reactions and provide needed reassurance. Understanding the psychology of crisis, including the predictable phases and patterns, makes it easier to understand and take appropriate steps or actions to help move through the crisis and mitigate its impact. Crisis is inevitable, but understanding the psychology involved makes it much more manageable.

Mary Schoenfeldt

Mary Schoenfeldt, Ph.D., is an experienced emergency management professional who understands disaster trauma both professionally and personally. She was duty officer for a large partner city the morning of one of the most catastrophic disasters in Washington State, and she was assigned the role of developing and coordinating disaster stress management services for the emergency operations center (EOC) staff. She has helped develop programs and has responded within EOCs to provide services. She is currently working with several states around the United States as they develop emergency management peer support programs. She is the board president of Green Cross Academy of Traumatology and has responded to countless disasters. She specializes in community and school crises and has a passion for disaster psychology. She is a faculty member of FEMA Emergency Management Institute, an adjunct faculty at Pierce College, and a subject matter expert for the U.S. Department of Education. She also serves clients through her consulting business. She can be reached at yoursafeplace@msn.com.

- Mary Schoenfeldthttps://domesticpreparedness.com/author/mary-schoenfeldt

- Mary Schoenfeldthttps://domesticpreparedness.com/author/mary-schoenfeldt

- Mary Schoenfeldthttps://domesticpreparedness.com/author/mary-schoenfeldt

- Mary Schoenfeldthttps://domesticpreparedness.com/author/mary-schoenfeldt